In New Orleans, children screen positive for post-traumatic stress disorder at three times the national average. There are many sources: experiences around Hurricane Katrina, exposure to violent crime, the buildup of family stress due to high poverty.

WWNO’s Mallory Falk and Eve Troeh have teamed up to report on the ways New Orleans schools have dealt with that trauma.

Part 1 of our series, “Kids, Trauma and New Orleans Schools,” explores how the city’s education reforms after Katrina have made it harder for some students to recover from trauma, and to learn.

If you know anything about New Orleans public schools, you probably know this: Hurricane Katrina wiped them out, and almost all the schools became privately run charters.

And you’ve probably heard about the education reformers who swept in to run those charter schools. People like Ben Kleban.

Kleban was like a lot of reformers. A white guy from outside New Orleans. He grew up in San Diego, worked corporate finance in Philadelphia, then totally scrapped that career and got into teaching.

“And really came into the adult world feeling a sense of desire and responsibility to serve and use the advantages I had had to help those who maybe weren’t as advantaged,” Kleban says. “And that’s what ultimately led me into education.”

Kleban, like a lot of reformers, saw Katrina as a tragedy but also an opportunity to build a new, better school system. One that held students to higher standards and set more of them on the path to college and out of poverty.

Kleban was recently sworn in an as a new member of New Orleans’ school board. But when he first came to the city, he started a charter school network, New Orleans College Prep, and took over three low-performing schools.

“And so we came out in our beginning years really as primarily sort of a 'no excuses' type of a model,” he says. “You know, a no tolerance, sweat the small stuff, a very rigid approach to discipline."

Sweat the small stuff. The idea that if you crack down on small misbehaviors, you can prevent bigger issues from erupting.

College Prep schools had strict rules about everything. Students had to sit up straight at their desks, eyes tracking the speaker. They had walk the halls in silence, and even wear the right kind of socks. Students who broke these rules, or acted out in other ways, got punished.

Kleban says the strict rules and discipline were meant to keep classrooms calm and keep learning on track. That was especially important because so many New Orleans students were far behind, academically. Charter schools in other cities sweated the small stuff and got results. Test scores, graduation rates, college acceptance all went up.

College Prep schools saw those gains, too. At first.

“But then I think we realized that even though we were able to get some academic growth in the first couple years, there was a number of kids who that really hard nosed discipline wasn’t helping them be successful," Kleban says. These are students who would be suspended multiple times for the same type of incident. And it wasn’t getting better. We weren't helping the child get successful, we were just enforcing a code.”

Kleban says about 20 percent of his high school students were getting suspended three times a year, or more. That told him that, for those kids, suspension wasn’t effective. Kicking them out of school didn’t “teach them a lesson.” It didn’t get them to act out any less. Plus, those students missed classroom time, and that meant they did worse on tests.

“So I think we really had to look in the mirror, and recognize what wasn’t working,” Kleban says.

Around the time Ben Kleban was opening his first charter school, a student named Antonio Travis was returning to New Orleans.

Travis was twelve when Katrina hit. His family fled to Houston, where they stayed in a series of shelters. It was hard to sleep at night.

“Just laying in shelters with people we don’t know and you seeing these old people, just watching people in the process of dying," Travis remembers. "And you know they can’t breathe, and you watching these people cry, and you have to lay next to them.”

Travis stayed in Texas for a few rough years. When he came back to New Orleans, the school system was totally different.

For high school, Travis enrolled in a brand new charter, Miller McCoy Academy. Like many, it promised that all students would go to college. Travis was excited. When he put on the uniform - a blazer and bow tie - he really felt like somebody. But soon, he started getting in trouble. He became a class clown, cracking jokes and interrupting his teachers.

“I’d tell a joke,” he remembers. “Class laugh. Teacher send me out the classroom.”

This happened over and over.

“Go to the principal. 'It was you again? Go home. You suspended.' And it’s just, that’s what it was.”

Travis says he needed to process what he’d been through from Katrina. Plus, his dad had left the family. And his brother had run away from home.

“I had a lot of trauma,” he says. “And I got kicked out of class for it.”

His acting out was a cry for attention. He says he needed counseling.

“Holding so much in and then going to school and not being able to vent, not being able to talk about them things,” that was difficult, Travis says.

Sometimes when he was suspended, he got sent home. Other times, he got in-school suspension, and sat in a room by himself. He says no one ever asked or tried to understand what led him to act out.

That was the way it was at lots of New Orleans schools. So many children in New Orleans have been exposed to trauma. But the school system hasn’t accounted for that.

Paulette Carter is President and CEO of the Children’s Bureau of New Orleans, a mental health agency for kids and families.

“Generally there just was really not an understanding of how trauma impacts a child,” she says. “Teachers and school staff really looking at children through the lens of what’s wrong with that child, versus what happened to that child.”

Carter sees the problem clearly. “Behaviors have a reason. But often schools, because they have so many kids that they're dealing with and so many different issues, often don’t really think about the reason behind those behaviors.”

Mental health workers like her have learned a lot in recent years about how trauma changes the brain, and how that shows up in behavior.

“A kid who's been exposed to trauma, their survival brain, that fight or flight response is much more developed and stronger," says Carter. "Because that’s how they’ve had to develop to survive, right, they've had to adapt to their environment. So they're responding to threats on a constant basis."

So if a child gets up and throws a chair, or suddenly storms out of the classroom, “maybe there’s a threat that they perceived,” Carter says. “If I'm walking down the hallway and somebody bumps into me and I don't have a significant trauma history, I'm gonna say 'oh, sorry, excuse me.' Whereas a kid who’s been exposed to trauma on an ongoing basis, if somebody bumps into them that might be a threat. And so what happens is that survival brain takes over and that part of the brain that's reasoning and logic shuts down.”

New Orleans kids screen positive for post-traumatic stress disorder more than three times the national rate. That statistic comes from the Institute of Women and Ethnic Studies, which also found that up to half of New Orleans kids have dealt with homicide in some way. About 20 percent have actually witnessed murder. Not to mention the city’s high poverty rate - about 40 percent of kids living below the poverty line. And the high incarceration rate. Many kids have a parent behind bars – also a source of trauma.

But when schools punish disruptions, no matter the reason, that means they send traumatized students out of class.

And New Orleans schools were sending so many kids out of class that the Southern Poverty Law Center sued the school system in 2010. The focus was on students with disabilities.

Eden Heilman is a lawyer with the SPLC. She says one of the plaintiffs in that lawsuit was a boy who’d been shot. Once he’d physically healed, his school considered him fully recovered. But it wasn’t that simple.

“He would jump out of his seat,” she says. “He would talk back to the teacher. He would yell profanity. If he felt slighted by another student he took it incredibly personally and would feel kind of like he needed to retaliate.”

He got kicked out of several schools.

“None of the schools that he went to kind of took the time to figure out what were the limitations as a result of his own experience actually being the victim of gun violence,” Heilman says.

The lawsuit was settled in 2014. But not before many children pushed out of school wound up quitting their education altogether, wound up in prison, or wound up dead.

Now there are more supports in place for students with disabilities. But there’s still no policy that says schools have to accommodate trauma.

Let’s go back to Antonio Travis, the student who had a tough time after Katrina. He was the class clown who got suspended all the time. Travis did manage to make it through high school at Miller McCoy. He got into college, but he floundered and dropped out. He worked as a clerk at a dollar store for a while. Then he connected with a group called Friends and Families of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children. And he works for them now, as a paid advocate for students like himself. He uses his painful experiences to help them.

His school, with all its big promises? It gave up its charter in 2015, after it got an F on the state report card.

Let’s also get back to Ben Kleban and the group of schools he started, New Orleans College Prep. Kleban set out to lower his suspension rates. He enlisted Amanda Aiken, a principal at Crocker Elementary.

She dove into the attendance rates, enrollment, in-school and out-of-school suspensions. She keeps charts of these things up on the walls.

"So as you see in this office, we track everything," she says.

When she looked into the back stories of these children – the ones who kept getting sent out of class – she found that many had experienced trauma.

“Either had been exposed to some type of violent or volatile situation recently,” Aiken says. “Parents were in a state of crisis of some form whether it was homelessness or abuse or some parents were incarcerated.”

What did these kids need? It was clearly something other than the discipline model they’d been using.

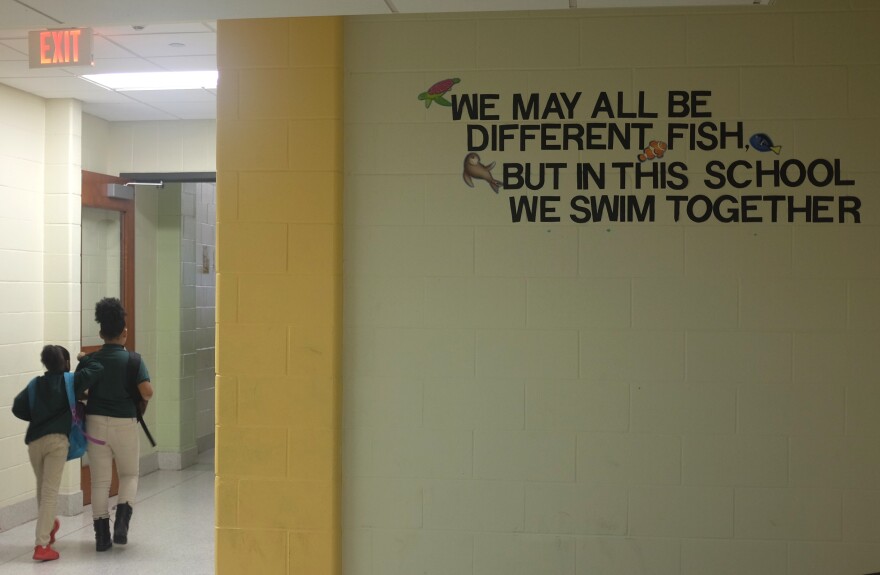

Crocker wanted to get away from that. But there was no clear path as an alternative.

“I couldn’t brand our approach to discipline as some kind of off the shelf model,” Ben Kleban says. “It’s certainly not 'no excuses' anymore, but I don’t know what it is. It’s actually, I think, just student focused. I think it’s just recognizing that every child is a human being with a unique personality, with a unique character, with unique experiences."

This might sound obvious. Every child is a human being, with unique experiences.

But making a school that can respond to every student’s emotional needs…that’s really hard. And results take time.

What did Crocker College Prep do? We’ll spend the next week focused on the changes that school has made, and the impact that’s had on students.

“Kids, Trauma and New Orleans Schools” was produced with support from the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Support for WWNO's Education Desk comes from Entergy Corporation.

Music in this story: "Little Black Cloud," "Raw Umber," and "Sepia" by Podington Bear.