The Episcopal Church of Louisiana spent the past year making plans for a new ministry, aiming to address its history of racism, as well as other forms of racism in society.

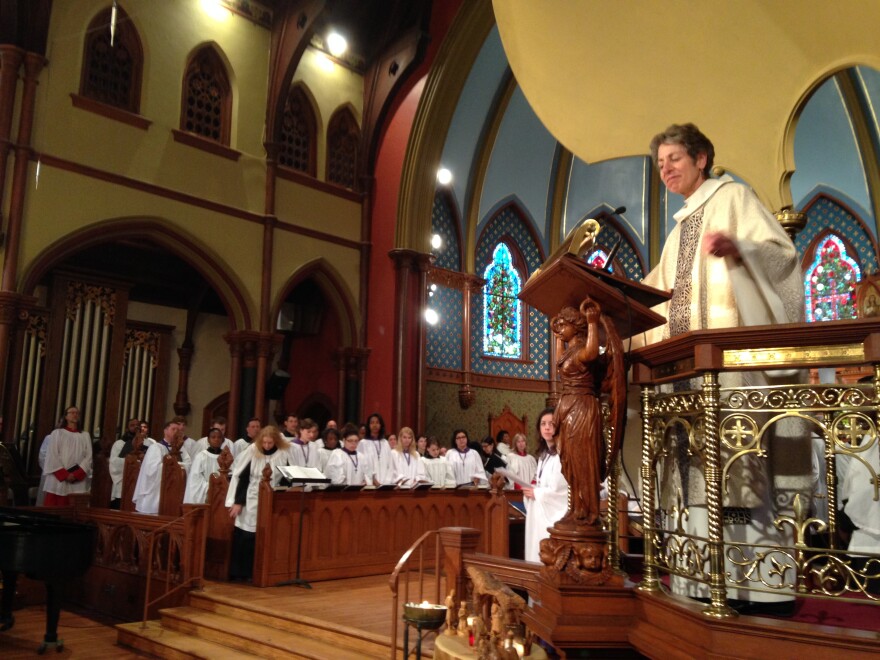

Last week, the Washington, D.C.-based leader of the Episcopal Church came to New Orleans for a special service. At Christ Church Cathedral, the oldest Episcopal congregation in New Orleans, worshippers committed to racial healing and racial justice.

Louisiana Bishop Reverend Morris K. Thompson declared 2013 as a year of reconciliation for the Episcopal Church. Over Martin Luther King Day weekend, the church inaugurated a year of increased activism. Bishop Thompson says this starts with awareness.

"This isn’t a service that I want people, and nor is it an intention to make people feel guilty, but to raise the awareness of who we are," says Bishop Thompson. "I don’t apologize for being a white male — I am by birth. It wasn’t a choice, but to not be aware of the benefit of that, I think is to live in my ancestors’ heads."

Dr. Katharine JeffertsSchori is the Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church. She came down to New Orleans to lead the service. She says during the Civil War many churches divided over the issue of slavery. But the Episcopal Church never split, because it never spoke out against slavery, in the north or the south.

"So the reconciliation work after the civil war was radically different than it was for the Methodists or Presbyterians," she says.

Bishop Schori has been outspoken on her policy of racial reconciliation on behalf of the church. OrissaArend serves on the Racial Reconciliation Committee. She’s a member of Trinity Church, and is blunt when describing the Episcopal community.

"The Episcopal Church was a church of the elite and has been and we still are. It's like a club, and when the other denominations came in, they appealed much more to the common man — so we remained the bastion and power and privilege."

Married couple Constance and Dane Perry came down to New Orleans from Boston specifically for this service. Constance is African-American, and a descendant of slaves. Dane has a different background.

"I grew up in Charleston, South Carolina," he says. "I used to do things back then that I am not at all proud of, and I’ve had the opportunity to have my eyes open to what the reality is, particularly in sharing my life with Constance. And that’s what this work is about — it’s about truly understanding the past so that we can understand how we’ve gotten so terribly stuck where we are today with regards to race, and move forward through a service like this morning."

The church was packed for the service, with members of congregations from all over the city. During the service the committee asked the congregation to commit to a new ministry, with focus towards race and reconciliation.

A sermon from the Dr. Schori addressed the history of slavery in Louisiana, and the church’s relationship to it.

"The particular challenge of Episcopalians here and across the church is to acknowledge our complicity in the institution of slavery," Schori said. "That the church here in Louisiana began and continued as a wealthy white proclaimer of a gospel of obedience, and a loyalty to a system of domination."

Music played a large role, with the choir singing roughly a dozen hymns. Tyrone Chambers II is a New Orleanian who now lives in New York. He also serves on the racial reconciliation committee, and flew down just to sing in the choir. He reflected on the service at the following reception. "One can never know the effects it will have, or what people will do with the information and the things they heard here after today, but I was happy to hear the bishop speak honestly and be forthright, because all the time people don’t get the point of gathering for this service."

Some people who, as Tyrone says, 'don’t get the point' have left the church. These ex-church members feel that having these discussions is what creates a problem that otherwise doesn’t exist. But the Episcopal leadership urges that it’s ultimately about getting involved in real issues outside of the church — like educational inequalities, mass incarceration, and slavery today, such as human trafficking.

But what needs to be done inside the church? Orissa Arend is grappling with this question.

"Do we become more welcoming, do we sing more black spiritual hymns? How do we learn to actually share power and decision-making? How do we work in partnership and true equality in the moral issues that are before the city?"

For Constance Perry, it’s not just about forming a more diverse congregation.

"I don’t think it’s about packing the pews with more people who look like me," she says. "I want an acknowledgement on behalf of the church of the history, because when the church does that that sends a message to me as an African-American, and it sends a message to other African-Americans, whether they’re Episcopalians or not. It sends a message."

A message that it is necessary to acknowledge the past in order to move forward with the Episcopal Church’s goal of being more involved in the community.